Douglas Trumbull Discusses the Preservation of the Epic Theatrical Experience

Shut up. Don’t talk. Listen. Watch. As an audience, we place so much emphasis on the plot of a movie that we forget that it’s a movie. Moving pictures. That’s why we’re here. Taking a journey with a cast of characters is wonderful, and empathizing with their trials and tribulations is essential to any narrative worth telling, but a plot can be crafted in any manner of mediums. If we’re going to bother to make a movie, then let’s embrace the defining characteristics of the art form. Go big or go home.

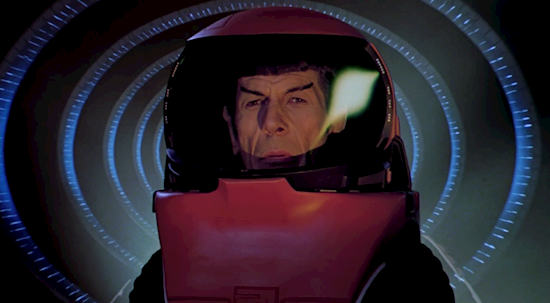

Douglas Trumbull has contributed to some of the most significant science fiction epics in cinematic history. His work with Graphic Films on the New York World’s Fair exhibition documentary To The Moon and Beyond caught the attention of Stanley Kubrick in 1964, and he soon joined the production of 2001: A Space Odyssey. Once onboard the production, Trumbull worked his way from designing the computer screen animations on the Discovery to concocting the film’s most memorable moment — the Star Gate sequence — which required the development of slit-scan photography. That alone would elevate any creative to legendary status, but from there Trumbull went on as special photographic effects supervisor on The Andromeda Strain, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Star Trek: The Motion Picture, and Blade Runner. Along the way, he also directed numerous films, including Silent Running and Brainstorm, and developed numerous technological advancements within the industry.

We do not take the opportunity to talk with Trumbull over the phone lightly. Without his input, the landscape of cinema would appear radically different. His insight on the industry is incredible, and he is actively engaged in today’s process of elevating the theatrical experience. As the delivery system for movies evolves, the filmmaker worries that we’re losing the emotional power of a 70mm Cinerama epic. There is no home for The Star Gate in mall multiplexes or on your iPhone, and the result is modern films that cannot be bothered with lingering feasts of cosmic thought. This is worrisome.

Have no fear; there is a fight in progress. Returning films like Star Trek: The Motion Picture into theaters, as Fathom Events is doing on September 15th and 18th, gives audiences an opportunity to soak in the majesty of the image. Our conversation with Trumbull begins with this often misunderstood film and its role in shaping the art form. Director Robert Wise was not only shepherding a cherished franchise from the boob tube to the silver screen, but he was also saving Paramount Pictures from potential disaster and allowing Trumbull to develop crucial technology.

The experience working with Kubrick altered Trumbull’s perception of cinema. Story remains king, but the image is story. As he progressed through his career, he brought that philosophy into every production whether the audience was prepared for it or not. Star Trek: The Motion Picture is a languorous human exploration that happily grinds to a halt for resonance and mood. The film is certainly not the cowboys in space adventure originally conceived by Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry in 1966, but it is an obvious extension of the frontier grandeur sought in 2001: A Space Odyssey. If you have not seen the film in a while, it’s time for a revisit.

Here is our conversation in full:

Set the scene for me: Star Trek: The Motion Picture. If I recall you were initially not interested in doing the project after Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

Well, I was already under contract to Paramount. I had set up a completely different company called Future General Corporation, which was a research and development subsidiary of Paramount. So, I was on their payroll. The whole idea for this company was to try to explore the future of cinema, and the future of new forms of entertainment. I was otherwise occupied, and I did not sign on with Paramount to do visual effects contracting work, which was what they actually wanted for Star Trek.

My partner Richard Yuricich and I had done a number of films previously, and he was hired by Paramount as kind of a consultant to figure out how to restore the production of the visual effects for Star Trek, because it was under a contract with Robert Abeland Associates. They were trying a really old and kind of dangerous approach, which was to explore the use of digital effects for the movie in digital pre-visualization, and it wasn’t working. They’d spent quite a lot of money and more than a year of their time and hadn’t gotten one shot done or made much progress. So, the studio was panic-stricken that they weren’t going to make their release date, so they asked if I would do the effects. I said, “Well, I don’t really want to do the effects for this. I don’t do contract effects generally, but I’m not under contract to Paramount to do the effects. So, the answer is no.” Do you know the story about the class action lawsuit against Paramount?

I’m aware of it, but I don’t really know the details of it.

It’s kind of a grizzly story because Paramount had taken a very large advance from the exhibitors, who had paid in advance for the rights to show the movie. Meaning part of the production budget of the movie was financed by exhibitors, who paid for the right to run it.

They were really disturbed when they heard through the grapevine that the movie might not be delivered on time. So there was a threat, and I don’t even know the details. You’d have to be a really hot investigative reporter to figure it out. But whether it was through NATO, which is the National Association of Theater Owners, or some other organization, I don’t know. They said, “If you don’t get this movie delivered, the movie we paid for, we’re going to close the theaters for the Christmas holiday and file a class action lawsuit against Paramount Pictures to kill blind bidding altogether,” which was the term that they used for these prepayments.

Exhibitors would pay in advance for a movie that they didn’t know what it was, it was just kind of a pool of funds. Star Trek was one of those, and Paramount was terrified that they were going to not only get sued but lose a lot of money and be professionally embarrassed in the industry. It would actually damage the whole industry to kill blind bidding.

So I got asked to go to an emergency meeting at Paramount with the entire legal staff at Paramount and my own lawyer to talk about “could we come up with some accommodation to get this done.” I said, “Okay, we’ll have a meeting.” And I brought my lawyer along. And I think it was Barry Diller who kind of made this speech to all of those in attendance, including Bob Wise, who was there, that they had this big problem. He explained the problem, and he said, “We have to get this movie done. I don’t care anything about whether it’s good or bad, or it’s missing scenes, or it makes no sense, but we must deliver on time. Period. So you got to figure out how to do it.”

That put me in a very good negotiating position to agree to do the movie in exchange for getting back the rights to everything I’d been developing at Future General Corporation, which included the Showscan 60 frame-per-second film process, and the whole concept of simulation rides, which was later used for Star Tours and Back to the Future: The Ride, and the video game concept we’ve developed, and another digital compositing video-based virtual set thing where we were superimposing actors into miniature sets in real time. That was used on the Cosmos television series. We were exploring some pretty advanced media technologies at the time, and I didn’t want to stop doing that. I didn’t want to put it on the back burner. I finally agreed to do Star Trek in exchange for having those things back. So I had control, and I would be released from my employment contract.

Source: filmschoolrejects.com