How 'Gretel & Hansel' Flips the Fairy Tale Script

[This story contains spoilers for Gretel & Hansel]

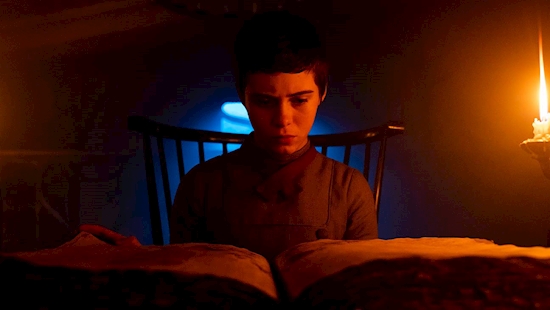

It’s a big bad world out there and the latest film from horror director Oz Perkins gives us just a taste of it. Orion Pictures’ Gretel & Hansel is a reimagining of the well-known Grimm’s fairy tale, Hansel and Gretel, that sees two orphaned siblings Gretel (Sophia Lillis) and Hansel (Samuel Leakey) encounter a witch (Alice Krige) in the woods with her own designs for the children. In terms of narrative, the film’s deviations from the classic Brothers Grimm story are only slight. But in filling in the gaps of an already horrific tale, Perkins and screenwriter Rob Hayes give the familiar story a new sense of thematic urgency and frightful purpose.

Heat Vision breakdown

So much of the horror genre stems from fairy tales: sinister witches, hungry wolves posing as men, mer-folk, misunderstood beasts, and child-stealing creatures, all bound by particular sets of rules. The stories that enchanted us as children have found their way to frighten us as adults. So many of these fairy tales have lost their original bite, expressly because they have been adapted and had their edges sanded down in the efforts to match our changing notions of what’s suitable for children. Disney, of course, has been a large part of this process, straying from the original darkness and tragedy that comprised of the stories of The Brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen, and making products that are magical, yet safe. But there’s nothing safe about these stories, and Gretel & Hansel is evidence of that.

One of the things Perkins’ film has going for it is that it, surprisingly doesn’t have a Disney adaptation to contend with in order to struggle against pre-conceived notions. Still, the film doesn’t so much as depart from our awareness of these stories as work within them, and its PG-13 rating is evidence of that. This isn’t a film that rejects the idea of fairy tales being for kids, like the gorerific blast that is Tommy Wirkola’s Hansel & Gretel: Witch Hunters (2013), or masterpiece of fantasy and politics that is Guillermo del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth (2006). Rather, like Neil Jordan’s The Company of Wolves (1984), the film challenges the modern idea of what kids can handle and take away from these stories, something Perkins has discussed while doing press for the movie.

For many lovers of horror, like myself, fairy tales were our doorway into the genre and our first glimpse of the notion that happy endings come with a cost, something the film leans heavily on through its repeated mantra in that there’s no such thing as a gift.

Gretel’s opening narration expresses her knowledge of the traditional role women play in these stories, the end result being their awakening by way of a kiss from a handsome prince, at the cost of their freedom and dreamscape. Gretel & Hansel draws out the inherent horror of gender politics that exist within fairy tales, and moves Gretel’s coming of age in the forefront. Her role in this story is more than the saving of her brother and role as a maternal-figure, but the efforts to come to terms with her own destiny, and the power of femininity expressed by witchcraft. Rather than the witch, Holda, existing simply as an enemy, she is an expression of Gretel’s own insecurities and wisdom, the budding knowledge that witchcraft does not exist in a vacuum, but is a symptom, and cure, that ensures the survival of women in this “big bad world.” Gretel’s journey of self-discovery and her chess game with Holda, both literal and figurative, is her eventual understanding of the concept “as above, so below,” in which taking something from one level of reality has the same effect, or cost, on the next level. We see this concept come to fruition within the horrors that await in Holda’s basement, her home’s true kitchen and dining room.

The coming of age aspect and a young woman’s discovery of her powers puts Gretel & Hansel in the conversation with Robert Eggers’ The Witch (2015). But the difference between the two films is suggested by their respective subtitles, “A New-England Folktale” and “A Grim Fairy Tale.” Eggers’ film relies on a sense of accuracy in its language and period setting that positions the film as a kind of cultural artifact, tied to the America of the 1630s. It is a marker, of time and place. Gretel & Hansel on the other hand eschews accuracy and a fixed placed in time in favor of a pot-pourri of aesthetic influences that make the film feel like something out of time. From its use of language, its costuming, and immersive synth score by composer Rob, Gretel & Hansel feels far more fantastic and distinct from any reality in which we could define by setting or time.

The dream-like essence of the film, which does far more to enhance the film’s style than to complicate it’s rather straight-forward narrative, makes the film feel like a much closer companion to Panos Cosmatos’ Beyond the Black Rainbow (2010), and Mandy (2018), than The Witch. Like those films, Gretel & Hansel is a film that feels both modern and somehow dug out of the past, an anachronistic phantasmagoria that is ultimately about characters becoming the beings they were always meant to be. Perkins leaves behind a trail of bread crumbs leading to a larger world in which fairy tales and horror overlap in a realm of otherworldliness that enriches and intertwines both.

HEAT VISION LATEST NEWS

View All1.

How 'Gretel & Hansel' Flips the Fairy Tale Scriptby

2.

'Scare Me': Film Review | Sundance 2020by

3.

Podcast Playlist: Gunpowder & Sky Veteran Joins Podium Audio, Richard Plepler Added to Luminary Boardby

4.

Susan Sarandon, Christina Ricci Celebrate Illusionist-Themed Roger Vivier Short Filmby

5.

Fox vs. Roku May Set "New Precedent" for Carriage Fightsby

Source: www.hollywoodreporter.com